The world of fungi only recently made its way into the mainstream, but this vast kingdom that exists all around us has deeply and powerfully enriched the Earth for millions of years. While fungi may often go unnoticed, their exceptional properties and ecological functions shape almost all living systems, including ours. Let us briefly explore the invisible realm of fungi, and uncover their remarkable potential for addressing many of the pressing environmental challenges we face today.

‘All Mushrooms Are Fungi, But Not All Fungi Are Mushrooms’

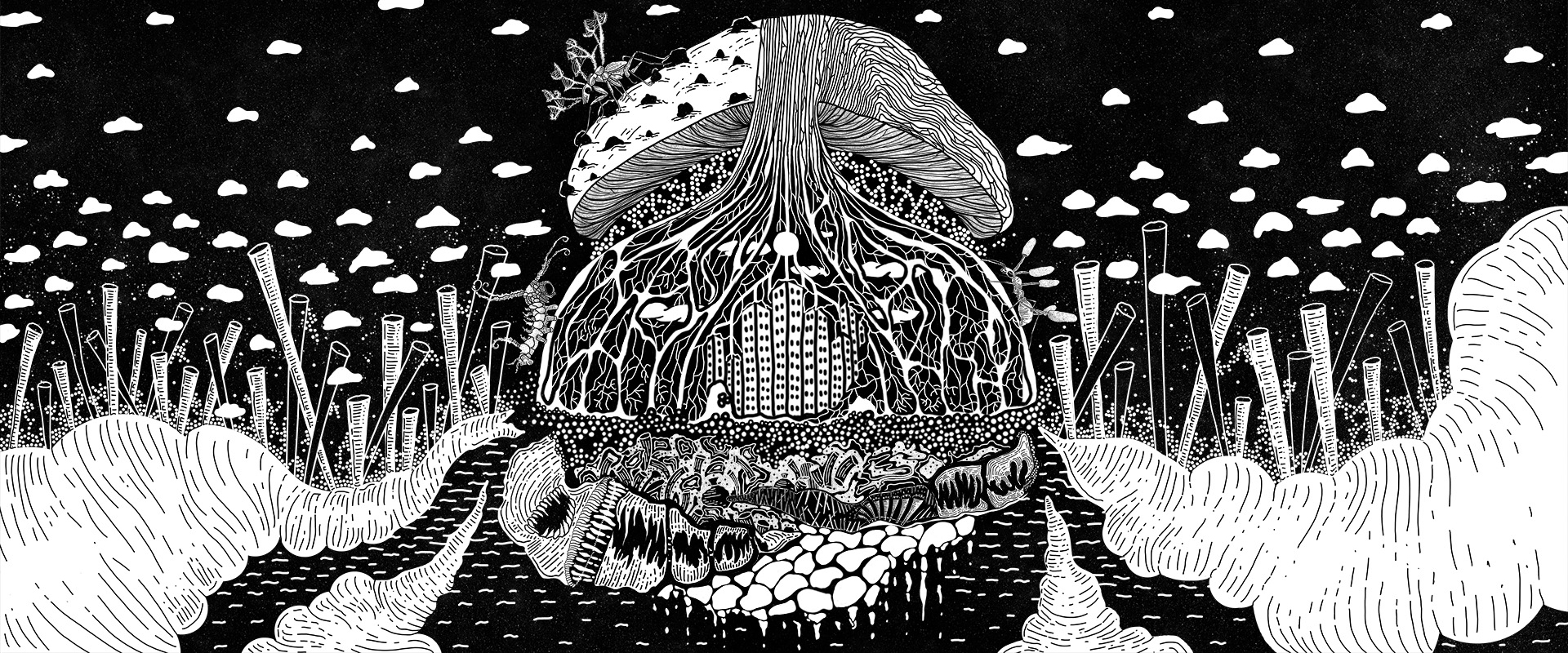

The fungus is created by hyphae that group together to form the “Mycelium”, a web-like structure that embeds itself in its host, which is usually soil, trees, fallen logs, and other diverse organisms. They are ubiquitous – found everywhere, if you look closely enough, and theoretically, it can live forever, as long as it has food to grow into.

Mushroom, on the other hand, is the fruit body of the fungus; similar to how apples are the fruits of an apple tree. Mushroom features consist of a cap, gills, and a stem, however, not all mushrooms include all of these features. It bears spores, which are microscopic and come in different shapes and colors, ranging from green to pink, white, and brown.

The mushroom also serves as the official reproductive organ of the fungus. When it matures, it releases millions, even trillions, of spores into nature, often forming dust-like clouds that disperse into the environment. A truly phenomenal wonder of nature.

Nature Calls, Fungi Answers

To begin with, Saprobic Fungi can break down dead organic materials such as fallen logs, twigs, dead animals and other matter found in forests, and recycle them back into the earth. Through their exceptional ability to decompose forest debris, they release nutrients back into the environment.

In fact, there exists a symbiotic exchange of nutrients between some fungi and their hosts. For example, Mycorrhizal Fungi, abundant at the root level of trees, helps them grow and develop by offering them nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Otherwise, the trees wouldn’t be able to absorb the nutrients as efficiently on their own. In return, the trees offer fungi sugars as a way of saying “thank you for your help”, establishing a mutually beneficial relationship.

Last but not least, Parasitic Fungi are a group that preys on other organisms, including other mushrooms. Cordyceps, for instance, specialize in invading insects, manipulating their behavior by flooding their brains with a chemical (like the ‘Last of Us’ TV series). They use insects as vehicles to spread their spores, which serve as their reproductive units, and can ultimately destroy entire colonies3.

Heroes with Cap

Outstanding support can be offered by a fascinating community of living organisms that inhabits a kingdom not so far away. Extensive studies have shown that fungi can help us remedy the environment by reversing the damages caused to it. Allow me to break it down for you:

One of the many powerful characteristics of fungi rests in its ability to restore degraded ecosystems. As already mentioned, fungi can boost soil quality and limit its erosion by unlocking nutrients in the soil, making them available to plants. They also assist in the diffusion of water, keeping the soil and plants hydrated. This can prove to be crucial in the process of healing forests that have been decimated by wildfires, for instance. Additionally, not only do they enhance soil and plant productivity but they also promote coexistence among species, which makes them integral to biodiversity regeneration.

In fact, certain parasitic fungi can act as natural fertilizers, helping to improve crop yields. This is because they naturally control insects and weeds without the use of harmful chemical compounds that deplete the land, contaminate water, kill biodiversity and even harm human health, providing a sustainable approach to agriculture.

Underground fungi also act as natural carbon sequestration machines, trapping massive amounts of carbon, the primary contributor to climate change4. Even after their death, the ecological benefits of fungi persist: they leave behind a network of dead tissue called ‘necromass’, which helps stabilize the soil by locking in the carbon and even preventing it from being released back into the atmosphere for a long time5. This is not to say that all answers to solving climate change can be found in fungi carbon, but unlike humans, they do play a part. We, on the other hand, have not done what we can to reverse the current greenhouse gas emissions trajectory and stop environmental pollution.

Cleansing the environment of toxic substances requires a wide range of efforts. The good news is, fungi’s function of decomposition goes beyond the transformation of decaying organic waste, as previously mentioned. Fungi have also proven to be active agents of nature that can absorb and eliminate heavy metals, petroleum waste, and even feed on radiation, all through bio-accumulating the contaminants in their bodies using fungal enzymes6. This ‘mycoremediation’ process makes certain types of fungi very effective in restoring soils and bodies of water that have been contaminated by pesticides7, oil spills, and various hazardous substances poisoning nature.

Over the past couple of years, successful experiments have finally demonstrated the potential of some types of mushrooms to eat plastic8, most of which is impossible to recycle. What’s more is, mycelium-based materials have been taking center stage as a potential revolutionary alternative to plastic and other unsustainable products of various industries such as leather textiles9, meat production and building materials10.

There is still a long way to go when it comes to fully comprehending how this vast kingdom works. What is certain, is that below our feet lies an enchanting form of life possessing diverse functions and services that make them not only an intriguing part of nature – but an indispensable ally in the quest for a more sustainable and balanced world.